What is the Difference Between Lean Body Mass and Muscle Mass?

category: Health Optimization

Editors note: This article has been re-published from an original article at InBody USA

Consider the following three statements:

- “I’m not working out to get huge; I just want to build strength and put on five pounds of lean muscle.”

- “My goal is to workout more and put on a healthy five pounds of muscle mass before next season.”

- “I’m going to add more protein to my diet and hopefully gain 5 pounds of lean body mass by the end of the month.”

In each one, someone wants to gain five pounds of something but is using three different terms. Are these three ways of saying the same thing? Can they be used interchangeably? Or are they different?

Let’s get one thing out of the way: “lean muscle” is a bit of a misnomer. Although there are indeed different types of muscle, from a biological point of view, there is no such thing as “lean muscle”. The word “lean” is usually meant to suggest the absence of body fat. But here’s the truth: all muscle is “lean muscle”.

What about Lean Body Mass and Muscle Mass? Both of these exist. However, they are two very different parts of your body composition, and in order to understand your weight, health, and fitness goals properly, you’ll need to understand the differences between them. Let’s take a look below.

Lean Body Mass Vs Muscle Mass

Lean Body Mass (also sometimes known as simply “lean mass,” likely the source of the word “lean muscle”) is the total weight of your body minus all the weight due to your fat mass.

Lean Body Mass (LBM) = Total Weight – Fat Mass

LBM includes the weight of:

- Organs

- Skin

- Bones

- Body Water

- Muscle Mass

Unlike lean muscle, Lean Body Mass correctly uses the word “lean” as it describes the entire weight of your body minus fat. This is why it is also known as “Fat-Free Mass.”

Because your Lean Body Mass comprises so many parts, any change in the weight of these areas can be recorded as changes in LBM. Keep in mind, the weight of your organs will not change much. Bone density will decrease over time, but it won’t significantly affect the weight of your LBM.

Two major areas to focus on with Lean Body Mass is body water and muscle mass.

When people talk about gaining muscle by eating more protein or muscle building workouts, what they’re really talking about is gaining or building their Skeletal Muscle Mass. This is because of the three major muscle types – cardiac, smooth, and skeletal – skeletal muscle mass is the only type of muscle that you can actively grow and develop through proper exercise and nutrition.

But Skeletal Muscle Mass is one part of your Lean Body Mass. Another major influencer is water and this can be a problem when people use muscle gain and “lean gains” interchangeably.

The Problem with “Lean Gains”

Because an increase of Skeletal Muscle Mass is an increase of Lean Body Mass, people will lump them together as “gaining lean mass” or “lean gains.”

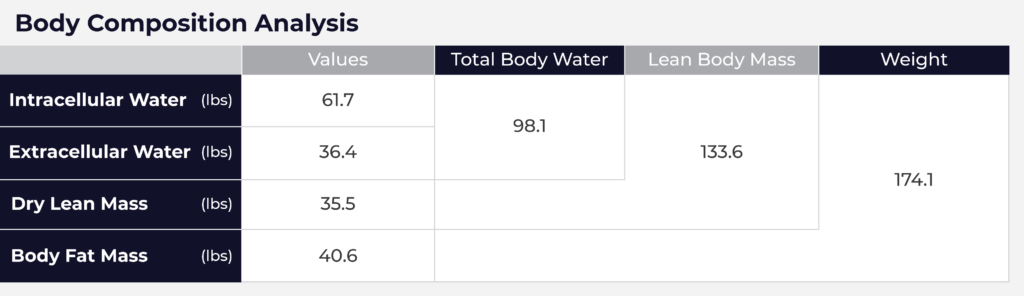

However, it doesn’t work the other way: an increase of Lean Body Mass is not always an increase in muscle. That’s because body water makes up a significant portion of your Lean Body Mass. To illustrate this point, here’s a body composition analysis of a 174.1-pound male.

98.1 (Total Body Water) + 35.5 (Dry Lean Mass) = 133.6 Lean Body Mass

Water made up more than 70% of the total body weight, which is normal for healthy adult males.

Notice how from a body composition standpoint, Lean Body Mass is made up of three components, two of which are water. Everything else is grouped together in what’s called your “Dry Lean Mass,” which includes your bone minerals, protein content, etc.

Muscle gains definitely contribute to LBM gains, but so does water, which can fluctuate throughout the day. For instance, this means that if you were to drink a significant amount of water, enough to raise your body weight by one pound, this weight would technically be a “gain” of lean mass.

It’s also important to note that muscle itself contains water – a lot of it. According to the USGS, muscle can contain up to 79% water content. Research has also shown that resistance training promotes the increase of intracellular water in both men and women.

All of this points to two main problems when talking about “lean gains”:

- Big Lean Mass gains, when it occurs quickly, are largely increases in body water

- It’s difficult to say with any certainty how much any gain in Lean Body Mass is due to Skeletal Muscle Mass without using the right tools

Since there’s a significant difference between Lean Body Mass and Skeletal Muscle Mass, how is it possible to know how much of each you have?

Let’s start with what not to do: do not try to use a scale to calculate changes in Skeletal Muscle Mass.

It’s a popular method to estimate muscle gain using a combination of the number on the scale and advice from fitness magazines.

The problem with using a scale to estimate progress is there are so many factors that can influence an increase in body weight, a few of which include:

- An undigested meal or drink

- Water retention due to glycogen

- Water retention due to sodium

- Body Fat gain due to being in a caloric surplus

There is only one way to calculate what is happening to your Lean Body Mass: getting your body composition analyzed. Without testing your body composition, there will be no way to know what any gain or loss in your body weight is due to.

Most methods of body composition analysis will at the minimum divide your body into Lean Body Mass (this may be referred to as Fat-Free Mass) and Fat Mass. These methods include:

- Skinfold calipers

- Hydrostatic Weighing

- Air displacement plethysmography

Each of these has their pros and cons, and accuracy may vary depending on a number of factors unique to each testing method.

For more in-depth body composition analysis, you would need to look to two more sophisticated methods: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) and Direct Segmental Multi-Frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis (DSM-BIA). Not only will these methods tell you how much fat you have, but they will differentiate your skeletal muscle mass from your lean body mass.

So, Lean Body Mass, Muscle Mass, Lean Mass, Which Is it?

Back to our originally three statements: which is correct to say? Let’s review:

- Lean Muscle: You should stop using this term because it is misleading. All muscle is “lean muscle,” and it is a confusing mix of two real terms: Skeletal Muscle Mass and Lean Body Mass.

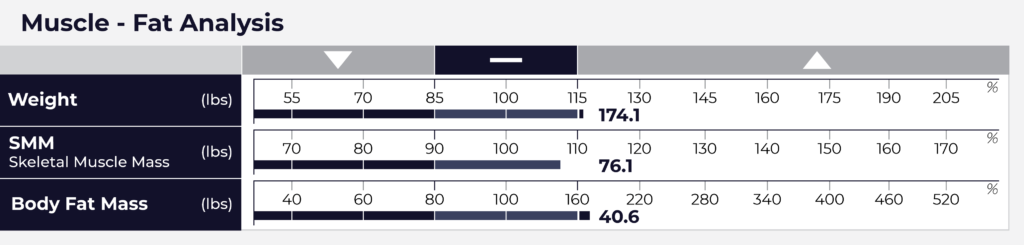

- Muscle Mass (or Skeletal Muscle Mass): Yes, it is likely true that if you’re performing resistance training/weight lifting workouts and adding enough protein to your diet, a percentage of the change is likely due to muscle mass development. But remember that skeletal muscle mass is part of LBM. Things get tricky when you start putting numbers on your muscle mass gains. Everyone’s body composition is different, and the proportion of your skeletal muscle mass to Lean Body Mass will not be the same as someone else’s. This makes accurate estimations even harder unless you have access to sophisticated tools that can differentiate between LBM and SMM.

- Lean Mass (lean body mass): This is probably the best and safest term to use to describe your gains. When you use this term, you’re telling people that you have gained weight from muscle and water, not body fat.

However, that’s all you can really say. Because of the nature of Lean Body Mass, it is very hard to say how much of the gain is due to water and how much is due to muscle (which is largely water to begin with). A gain of 5 pounds of LBM is not 5 pounds of pure muscle,

When it comes to tracking your muscle gain (or fat loss), it all comes down to what tools you’re using to measure your progress. If all you are working with is a weight scale, then all you will ever know for sure is your weight is increasing or decreasing. It would be hard to differentiate the weight gain from water, muscle, or body fat. If you are serious about accurately measuring your muscle gain and assessing your health, go get a body composition analysis. Then – and only then – can you tell people that you gained five pounds of muscle with confidence.